Teacher Workload and Adaptive Learning

How adaptive learning can help maximise the impact of feedback and reduce teacher workload

The aim of this post is to provide a summary of some of the current research into marking and feedback to enable you to have informed discussions at your school and hopefully reach a sustainable workload for you and your colleagues. I’ll also outline how adaptive learning programs, using Mathspace as my example, can be the ideal solution to the problem of feedback-generated workload.

Who am I and why am I interested in teacher workload?

I did not consider becoming a teacher until university. To be sure it was what I wanted to do, I worked for a year as a teaching assistant and upon completing my teacher training, I started as a Newly Qualified Teacher (NQT) at a school in Sevenoaks. I was made the Maths Lead the next year before also becoming the Data and Assessment Lead, taking on an extra workload that tipped the scales of my work-life balance.

When I decided to leave teaching, I assumed that all schools were like mine — that they all insisted on marking every piece of work and providing written feedback; daily in core subjects and weekly in foundation subjects. I assumed all schools tested students and entered data on a termly basis, believing all of this was the only way to improve progress and attainment. I never considered that there could be another option.

What does the research on feedback say?

To tackle the issue of feedback-related workload, we need to consider the two ideas behind why we provide feedback to our students:

- Feedback allows the learner to see their mistakes, rectify them and thereby learn from them, which will lead them to avoid those mistakes in future.

- The teacher can identify any misconceptions and address them with individual learners, groups of learners or even the whole class as necessary.

There is no doubt that the argument for providing feedback is strong. Powerful forms of feedback have been shown to accelerate progress by over 100% and students can make 24 months progress in just 12 months, though the quality of evidence for this is varied. The problem is, not all forms of feedback are equal and the weaker of these can even negatively impact progress.

In addition to identifying the most powerful forms of feedback, we must manage the workload of giving feedback; striking a balance between what is effective and sustainable. The current rate at which teachers are leaving the profession can often be attributed to workload: 40% of newly qualified teachers have left within 5 years, with the number jumping to 50% for ‘high-priority’ subjects like physics and maths.

To summarise the research on feedback, I looked at several sources (the full list can be found at the end of this post). I will be focusing on three documents:

- OFSTED’s “Clarification for schools” document

- The Education Endowment Fund’s report, “A marked improvement?”

- John Hattie and Helen Timperley’s report, “The Power of Feedback”

Firstly, let’s look at the myth-busting document produced by OFSTED (Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills): “Clarification for schools.” The most important point, with regards to feedback, is that OFSTED doesn’t expect a “specific frequency, type or volume of marking,” or “any written record of oral feedback,” but feedback, “should be consistent with [the school’s] policy.”

The EEF’s paper, “A marked improvement?” attempts to summarise the current research into marking, pointing out that “the quality of existing evidence on written marking is low” — an industry wide issue which Ben Goldacre’s “Building Evidence into Education” brilliantly delves into. Despite this lack of quality evidence, the report did find evidence of more and less valuable techniques.

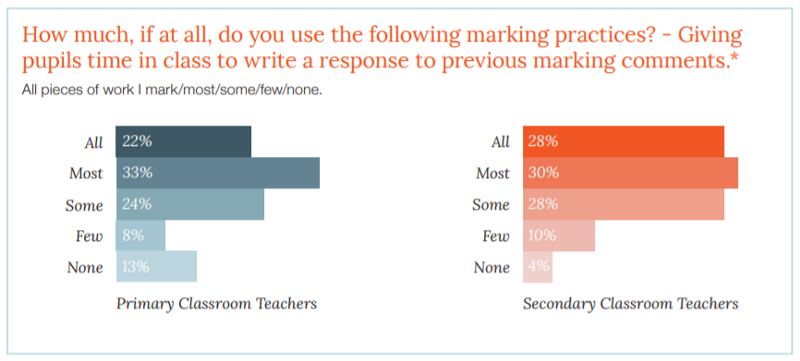

One of the key points highlighted in the paper was that marking is unlikely to have any effect if students aren’t given time to respond to it. This may seem obvious and yet, even though teachers in England spend nearly 130 million hours a year on marking, as shown below, the majority are not giving pupils time to respond to all that marking.

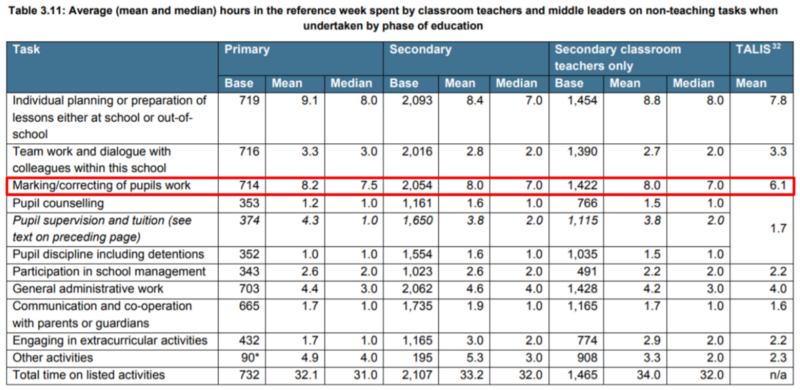

The mean average number of hours spent marking per week (according to the Teacher Workload Survey 2016) was 8 hours in secondary and 8.2 in primary. With an estimated 25% of marking going unresponded to (a pretty conservative estimate I expect), this adds up to around 2 hours a week, or 78 hours a year, wasted per teacher. With over 425,000 teachers in England alone, this works out be to over 32 million hours wasted annually.

There are two further points in the EEF report that lead to their conclusion that “schools should mark less … but mark better.” The first is that some forms of marking, such as acknowledgement marking, are unlikely to have any benefit for the learner. The second is that there is some evidence that “focusing marking on limited sections of a piece of work and correcting all errors” has a positive impact. The findings are important as we need to keep in mind both the best method for feedback and how to keep workload manageable.

John Hattie’s famous work, “Visible Learning”, was criticised for the meta-meta-analysis process which was accused of aggregating data into trends that missed finer details of the story. This process is much like concluding that the team that wins the league must have all the best players in the league — it is entirely possible that this is the case but it is not the only explanation. Building on “Visible Learning”, John Hattie and Helen Timperley’s, “The Power of Feedback” focuses on identifying the effectiveness of different forms of feedback.

This research found the most powerful forms of feedback are providing cues (with an effect size of 1.10); followed by providing reinforcement (0.95); feedback using video or audio (0.64); computer-assisted instructional feedback (0.52); and feedback relating to goals (0.46). Hattie and Timperley use Cohen’s d as a measure of effect size and argue that those forms of feedback over the average (0.4) are the ones we should focus on.

Hattie and Timperley also detail what they believe are the four types of feedback:

- The task or product: the answer given to a maths problem e.g. 3x = 9 and student submits x = 4, incorrect;

- The learning process: how to solve the maths problem e.g. 3x = 9, divide both sides by 3 to find the value of x;

- The learner’s self-regulation: encouragement to solve the problem in a way the learner is familiar with e.g. go back and think about how to isolate the x;

- The learner themselves: relating to ability e.g. you are a star.

Hattie and Timperley argue that feedback relating to the learner themselves is the least effective as it doesn’t relate to the learning in any way. They claim that feedback on the task or product is effective only when used for self-evaluation, though this use is rare. Finally, they argue that feedback about the learning process and the learner’s self-regulation are the most powerful as they cause the learner to think more deeply about how to solve the problem.

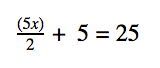

I would argue that feedback on the process is the most powerful as it links feedback to instruction. Feedback on self-regulation is also powerful as it directs the learner towards knowledge they already have, perhaps helping them to use it in a new context. I agree that task feedback must lead to self-evaluation to be effective but believe that this need not be rare. For example, if a learner is trying to find the value of x in the following equation:

and they are marked incorrect at the point at which they initially went wrong, they can potentially identify their mistake and enter the correct next step. Furthermore, we can increase impact by using self-regulation and process feedback as cues alongside task feedback, helping the learner to identify the next step when they cannot correct their mistake without any further input.

How does adaptive learning help teachers to deliver feedback?

Adaptive learning technology can help to maximise both the quantity and quality of every piece of feedback. Mathspace is different to other adaptive learning platforms in that it allows learners to enter all their working and gives feedback at this granular level, with both process and self-regulation feedback provided.

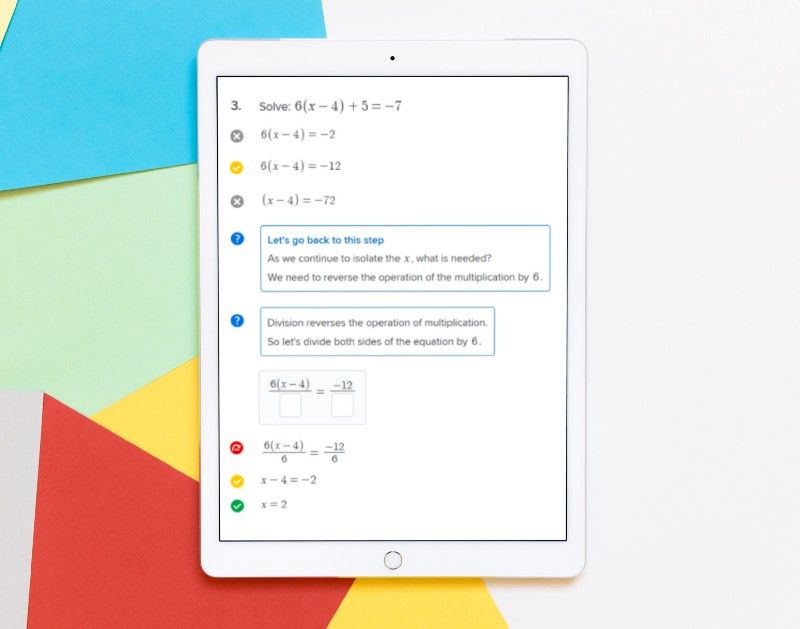

Feedback, in the form of a tick or cross, is given to the student at every step as they solve a question. Additional help, in the form of hints and videos, is also available to the student (if they need it). It’s important to note that the learner doesn’t receive any feedback (on the process) unless they ask for it. This allows them to identify the mistake themselves — turning the task feedback into self-regulation feedback. If the learner cannot identify where they have gone wrong, Mathspace can provide a hint which takes the form of self-regulation feedback, prompting the learner to think about what they already know. If needed, a second hint provides process feedback, explaining the process needed for the next step by using scaffolding, as shown below.

If the learner can’t complete this step after two hints, they can skip the step. This will provide the learner with the next correct step — in itself another example of process feedback. However, if they’ve skipped a step, how do we know that they have learned anything?

Mathspace overcomes this issue with another level of adaptive learning. If the learner completes the problem using skipped steps, Mathspace will present similar problems for the learner to prove that they’ve learned something. If the learner has demonstrated understanding, they will be given more challenging problems to test and extend their knowledge until they master that topic.

Mathspace’s adaptive learning technology can also identify other related areas that the learner may need to work on by using its knowledge graph. For example, if the learner is struggling with multiplying fractions by integers, Mathspace may recommend revision of “finding unit fractions of amounts” or, “multiplication as repeated addition.” This level of adaptive learning relates to some of Hattie’s other work on the importance of feedback to teachers (0.72) in planning future instruction — feeding forward.

Mathspace allows teachers to intervene and assign each learner the relevant content for them to differentiate instruction based on data. We’re working on automatically presenting this information to students to save teachers more time in the future, while maintaining the teacher’s ability to use their discretion to override and assign tasks they deem appropriate.

Developing a sustainable marking and feedback policy

Until the time when every school is able to fully utilise adaptive learning, a sustainable marking and feedback policy is required. For that reason, I’d like to finish off by outlining some suggestions for you to discuss with your colleagues to help you create a policy that all staff can agree on and implement.

- Scrap acknowledgement marking, including indication of verbal feedback being given — there is little to no benefit.

- Ensure all feedback, written or otherwise, is on process or self-regulation and is responded to by learners — if it won’t be responded to, don’t mark it.

- Partially mark work — this is perhaps better suited to literacy-based work but both saves time and provides learners the opportunity to self-regulate.

- Group books together to cover all attainment levels within the class and then mark one group each day — by grouping carefully, you can pick up on common misconceptions and provide feedback on these.

- Feed back to whole class on common misconceptions or errors — combined with careful grouping, this can ensure all students receive relevant feedback and informs your planning for future instruction.

- Utilise the power of adaptive learning programs, like Mathspace, to ensure all students receive powerful feedback on their work and to allow you to plan future instruction.

Works Cited

Ascd The Secret of Effective Feedback [Online]. Available at: http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/apr16/vol73/num07/The-Secret-of-Effective-Feedback.aspx.

Black, P. and Wiliam, D. Developing a Theory of Formative Assessment. Assessment and Learning:206–230.

Cohen’s d: How to Interpret It? (2018). [Online]. Available at: https://scientificallysound.org/2017/07/27/cohens-d-how-interpretation/.

Evidence on Marking [Online]. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/on-marking/.

Fuchs, L.S. and Fuchs, D. (1986). Effects of Systematic Formative Evaluation: A Meta-Analysis. Exceptional Children 53:199–208.

Graham, S., Hebert, M. and Harris, K.R. (2015). Formative Assessment and Writing. The Elementary School Journal 115:523–547.

Hattie, J. and Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research 77:81–112.

Higton, J. (2017). Teacher Workload Survey 2016: Research Report. Department for Education.

Higton, J. (2017). Teacher Workload Survey 2016: Research Report. Department for Education.

Key UK Education Statistics [Online]. Available at: https://www.besa.org.uk/key-uk-education-statistics/.

Kingston, N. and Nash, B. (2011). Formative Assessment: A Meta‐Analysis and a Call for Research [Online]. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2011.00220.x.

Kluger, A.N. and Denisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin 119:254–284.

Reducing Teacher Workload [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/reducing-teachers-workload/reducing-teachers-workload.

TEDxTalks (2013). Why Are so Many of Our Teachers and Schools so Successful? John Hattie at TEDxNorrkoping [Online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rzwJXUieD0U.

Teachers [Online]. Available at: http://mrbartonmaths.com/teachers/research/marking.html.

The Teacher Labour Market in England [Online]. Available at: https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/the-teacher-labour-market-in-england/.